Wild Side #01

Monsanto's Dark History: 1901-2011

2011; revised 2013

Dark History of the Evil Monsanto Corporation

Monsanto is the world's leading producer of the herbicide "Roundup", as well as

producing 90% of the world's genetically modified (GMO)

seeds.

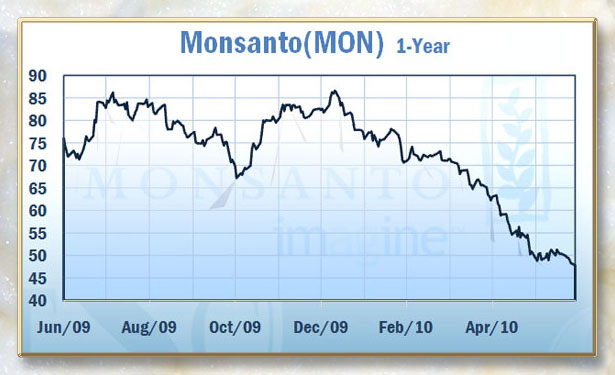

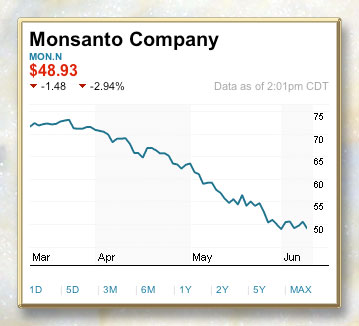

Over Monsanto's 110-year history (1901-2013), Monsanto Co (MON.N), the world's

largest seed company, has evolved from primarily an industrial chemical concern

into a pure agricultural products company. MON profited $2 billion dollars in 2009,

but their record profits fell to only $1 billion in 2010 after activists exposed Monsanto

for doing terribly evil acts like suing good farmers and feeding uranium to pregnant

women. Below is a timeline of Monsanto's dark history.

Monsanto, best know today for its agricultural biotechnology GMO products, has a

long and dirty history of polluting this country and others with some of the most toxic

compounds known to humankind. From PCBs to Agent Orange to Roundup, we have

many reasons to question the motives of this evil corporation that claims to be working

to reduce environmental destruction and feed the world with its genetically engineered

GMO food crops. Monsanto has been repeatedly fined and ruled against for, among

many things: mislabeling containers of Roundup, failing to report health data to EPA,

plus chemical spills and improper chemical deposition.

The name Monsanto has since, for many around the world, come to symbolize the

greed, arrogance, scandal and hardball business practices of many multinational

corporations. A couple of historical factoids not generally known: Monsanto was

heavily involved during WWII in the creation of the first nuclear bomb for the Manhattan

Project via its facilities in Dayton Ohio and called the Dayton Project headed by Charlie

Thomas, Director of Monsanto's Central Research Department (and later Monsanto

President) and it operated a nuclear facility for the federal government in Miamisburg,

also in Ohio, called the Mound Project until the 80s.

Documentary Movies About Monsanto

The World According to Monsanto (2008 – 01:49:02)

Directed by Marie-Monique Robin. Originally released in French as

Le monde selon Monsanto, the film is based on Robin's three-year-long

investigation into the corporate practices around the world of the United States

multinational corporation, Monsanto. The World According

to Monsanto is also a book written by Marie-Monique Robin — winner of the

Rachel Carson Prize — translated into many languages.

- watch at TopDocumentaryFilms.com

- watch at YouTube.com

- watch at YouTube.com

- watch at FreeDocumentaries.org

- watch at FilmsForAction.org

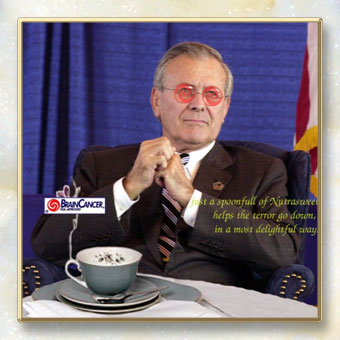

Sweet Misery: A Poisoned World (2004 – 00:52:00)

"This is a must see movie especially if you or someone you love are nutrasweet drinkers.

I was, and I'm not now. I was appauled at how this dangerous substance was approved by

the FDA in spite of the mounting evidence it caused brain tumors and other neurological problems.

If you think everything approved by the FDA is safe, you need to see this movie... politics and big

business are very powerful... education is power... empower yourself to take control of your health."

– D. Wright (June 25, 2006)

"The documentary Sweet Misery tells the whole story about aspartame, from its astounding list

of related adverse health effects to the corporate fraud and manipulation surrounding its approval.

Sweet Misery includes many heartfelt conversations with aspartame victims,

including one woman serving a prison sentence for poisoning her late husband, even though

his health signs suggest aspartame may have been to blame.

You'll also hear from medical experts, including Dr. Russell Blaylock, a renowned neurosurgeon,

who explain why aspartame acts as a poison to your brain and body.

But perhaps the most riveting aspect of the film is the evidence showing the extensive corporate

fraud and manipulation that lead to aspartame's approval. The film has archival footage from G.D.

Searle, the producer of aspartame, and federal officials describing the extensive propaganda used

to push aspartame on the market.

Additionally, dialogue from a former US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) investigator also

detailing the manipulation that took place to get this chemical approved will leave you with the

"big picture" of conspiracy and even criminal negligence surrounding this popular artificial sweetener.

There's even an exchange described with Donald Rumsfeld, who was the CEO of Searle and, at the

same time, part of Reagan's transition team when the FDA's board of inquiry was overruled to allow

the marketing of aspartame as a food additive. Prior to this time, aspartame was unanimously rejected

by the FDA because the scientific data just did not support it as a safe product."

– Dr. Mercola (review)

The Future of Food (2004 – 00:88:00)

"The Future of Food documents what is currently going on with the food supply in the US. Monsanto, a

multinational corporation who was formerly in the pesticide business (agent orange, ddt) is now one

of the biggest seed suppliers in the world. And not just any seed, it's genetically engineered for a number

of purposes.

Monsanto has been suing farmers who have not bought seed from them but end up with it growing in

their fields from no fault of their own. In one very well known case a farmer, Percy Schmeiser, was told

by his neighbor that the neighbor's truck had a hole it's tarp and a lot of Monsanto's' 'round up ready'

seed was dumped on his field. Monsanto tried to sue him (and many other farmers — google and you'll

see links to many of the cases) and he spent his life savings fighting them. He just recently won his case

after 10 years!

The film has wonderful and informative interviews with Andrew Kimbrell, director of the center for Food

Safety, Fred Kirshenman, a well known sustainable farmer, and a number of experts and scientists who

document first off how GE food was pushed on the American people with no disclosure and no testing as

well as the devastating potential for destruction with messing with our food supply for profit.

There's a lot we can do. Support small farmers and farmers market's. Join a community supported agriculture

program where you get a box of fresh from the field organic fruits and vegetables each week. We also

need to demand labeling. Right now we don't know which foods we buy are genetically altered and which

aren't. If our food is labeled we can make informed choices.

I highly recommend this film — it's important information for us all."

– Sheri Fogarty (review)

- film's web site

- watch the film's trailer

- watch at TopDocumentaryFilms.com

- watch at OnTheFutureOfFood.org

- watch at SnagFilms.com

- watch at BrassCheckTV.com

- watch at WatchDocumentary.tv

Monsanto Company History Overview

Monsanto is a US based agricultural and pharmaceutical monopoly, Monsanto

Company is a producer of herbicides, prescription pharmaceutical drugs, and

genetically engineered (GMO) seeds. The global Monsanto corporation has operated

sales offices, manufacturing plants, and research facilities in more than 100 countries.

Monsanto has the largest share of the global GMO crops market. In 2001 its crops

accounted for 91% of the total area of GMO crops planted worldwide. Based on

2001 figures Monsanto was the second biggest seed company in the world, and

the third biggest agrochemical company.

Historically Monsanto has been involved with the production of PCBs, DDT, dioxins,

and the defoliant / chemical weapon 'Agent Orange' (sprayed on American troops

and Vietnamese civilians during the Vietnam War). Originally a chemical company,

Until the late 1990s Monsanto was a much larger 'lifesciences' company whose business

covered chemicals, polymers, food additives and pharmaceuticals, as well as agricultural

products.

All of these other chemical business areas have now been demerged or sold off. Monsanto

sold its chemical business in 1997 to build a presence in biotechnology, developing

NON-ORGANIC GMO soybeans and corn (classified as a pesticide and banned in the

EU) to resist the poisonous effects of its Roundup herbicide. Monsanto's

key business areas are now agrochemicals, seeds and traits (including GMO crops),

Monsanto also produced NutraSweet,

a GMO sugar substitute. Monsanto recently sold it's GMO bovine growth hormones

monopoly to Eli Lilly, and sold it's aspartame business to Pfizer.

Monsanto's business is currently run in two parts: Agricultural Productivity, and Seeds

and Genomics. The Agricultural Productivity segment includes Roundup herbicide and

other agri-chemicals, and the Animal Agriculture business. The Seeds and Genomics

segment consists of seed companies and related biotechnology traits, and a technology

platform based on plant genomics. In reality of course these two segments are inseparable,

since the agri-chemicals are becoming increasingly dependent on the seeds segment

for sales.

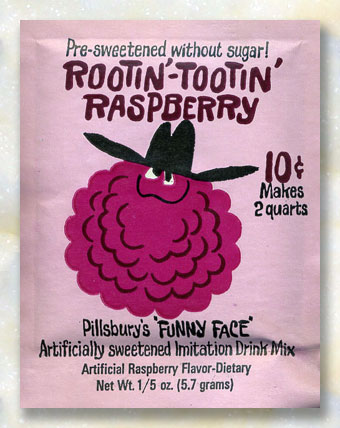

Monsanto's Early 20th-Century Origins

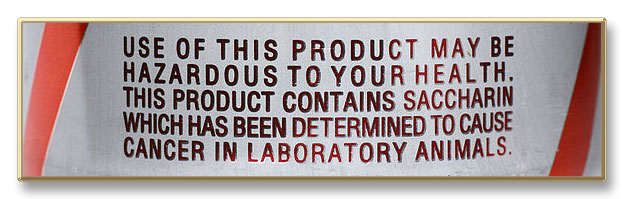

Monsanto traces its roots to John

Francisco Queeny, a purchaser for a wholesale drug house at the turn of the century,

who formed the Monsanto Chemical Works in St. Louis, Missouri, in order to produce the

artificial sweetener saccharin for Coca-Cola.

John Francis Queeny (August 17, 1859 – March 19, 1933) started work at age

12 for a wholesale drug company, Tolman and King. He attended school for 6 years until

the Great Chicago Fire forced him, at the age of 12, to look for full-time employment,

which he found with Tolman and King for $2.50 per week.

In 1891, he moved to St. Louis to work for Meyer Brothers Drug Company. John was

inducted into the Knights of Malta order. His first business, a sulfur refinery in East St. Louis,

was destroyed by fire on its first day of operation in 1899. The process of refining beet

sugar in 1900, led to Monsanto Corporation's first artificial sweetener, the following year.

Butter substitute, MSG and partially hydrogenated vegetable shortening were all soon to

follow.

John Francis Queeny married Olga Mendez Monsanto with whom he had two children,

one of whom was Edgar Monsanto Queeny, who would later serve as Chairman. In 1901,

John then established his own chemical company to produce the sweetener, saccharin,

which was only available in Germany at that time. He named the company Monsanto after

his wife's maiden name, Olga Monsanto Queeny.

Queeny was a member of the Missouri Historical Society and was a director of the

Lafayette-South Side Bank and Trust Company. "He was also known for his many

philanthropic endeavors." [Final Resting Place, p. 83, The St. Louis Portrait, p. 221]

Knight

of Malta John F. Queeny: Founder of Monsanto

According to the Count in Venice, John Francis Queeny (founder of The Monsanto

Company) was a Knight of Malta. Irish-American ROMAN Catholic Queeny (1859-1933)

founded Monsanto in 1901 within the Jesuit stronghold of St. Lewis — hosting the

Black Pope's Saint Louis University since 1818.

[See Knight

of Malta John F. Queeny: Founder of Monsanto by Eric Jon Phelps (July 7, 2013).]

This is the same year J. P. Morgan, Papal Knight of the Order of Saints Maurice and

Lazarus, founded U.S. Steel Corporation and in 1911 would appoint Knight of Malta

John A. Farrell as its president. Interesting: Queeny, Morgan and Farrell were all wicked,

pope-serving, White Gentiles — not a Jew in the mix!

Robert B. Shapiro was Monsanto's CEO from 1995 to 2000. The devil's Great Conspiracy

for world government must always appear to be led by Jews, never by the Pope of Rome

using select, Masonic "Court Jews" as his underlings!

Once the manufacturer of the now outlawed DDT and Agent Orange during Francis

Cardinal Spellman's CIA-directed Vietnam War, the company also developed and

now markets bovine growth hormone,

further poisoning the food chain here in America. It is most intriguing that Europe – the

pope's Revived Holy Roman Empire deceptively called "The European Union" —

refuses to purchase beef produced in the United States!

Upon purchasing G. D. Searle and Company in 1985, Monsanto, via its NutraSweet

Company, is the manufacturer of Aspartame,

the notorious neuro-toxin sold to the public as an artificial sweetener. Aspartame

is the "artificial sweetener" in the soft drink Diet Pepsi, Pepisico once employing

JFK assassin / FBI liaison to the Warren Commission and Knight of Malta Cartha D. DeLoach.

Monsanto also has strong ties to The Walt Disney Company, with financial backing from

the Order's Bank of America founded in Jesuit-ruled San Francisco by Italian-American

ROMAN Catholic Knight of Malta Amadeo Giannini in 1904. Disney owns ABC Television

Network and its Director Emeritus is Roy Disney (brother of the late Walt Disney) who

was inducted into the Knights of St. Gregory during the same ceremony with Fox Network

owner Rupert Murdoch. ABC and Fox are both controlled by Rome through brother Knights

of the Order of St. Gregory!

World War I: Petrochemicals

While prior to World War I America relied heavily on foreign supplies of chemicals,

the increasing likelihood of U.S. intervention meant that the country would soon need

its own domestic producer of chemicals. Looking back on the significance of the war

for Monsanto, Queeny's son Edgar remarked, "There was no choice other than to improvise,

to invent and to find new ways of doing all the old things. The old dependence on Europe

[Hitler's IG Farben in Nazi Germany] was, almost overnight, a thing of the past." Among

other problems, Monsanto researchers discovered that pages describing German chemical

processes had been ripped out of library books. Monsanto developed several pharmaceutical

products, including phenol as an antiseptic, in addition to acetylsalicyclic acid, or aspirin.

Under Edgar Queeny's direction Monsanto, now the Monsanto Chemical Company, began

to substantially expand and enter into an era of prolonged growth. Acquisitions expanded

Monsanto's product line to include the new field of petrochemical plastics and the manufacture

of phosphorus.

Postwar Expansion & New Leadership

Largely unknown by the public, Monsanto experienced difficulties in attempting to market

consumer goods. However, attempts to refine a low-quality detergent led to developments

in grass fertilizer, an important consumer product since the postwar housing boom had

created a strong market of homeowners eager to perfect their lawns.

Under Hanley, Monsanto more than doubled its sales and earnings between 1972 and

1983. Toward the end of his tenure, Hanley put into effect a promise he had made to

himself and to Monsanto when he accepted the position of president, namely, that his

successor would be chosen from Monsanto's ranks. Hanley and his staff chose approximately

20 young executives as potential company leaders and began preparing them for the head

position at Monsanto. Among them was Richard J. Mahoney. When Hanley joined Monsanto,

Mahoney was a young sales director in agricultural products. In 1983 Hanley turned the

leadership of the company over to Mahoney. Wall Street immediately approved this decision

with an increase in Monsanto's share prices.

1976, Monsanto announced plans to phase out production of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB).

In 1979 a lawsuit was filed against Monsanto and other manufacturers of agent orange, a defoliant used during the Vietnam War. Agent orange contained a highly-toxic chemical known as dioxin, and the suit claimed that hundreds of veterans had suffered permanent damage because of the chemical. In 1984 Monsanto and seven other manufacturers agreed to a $180 million settlement just before the trial began. With the announcement of a settlement Monsanto's share price, depressed because of the uncertainty over the outcome of the trial, rose substantially.

Also in 1984, Monsanto lost a $10 million antitrust suit to Spray-Rite, a former distributor of Monsanto agricultural herbicides. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the suit and award, finding that Monsanto had acted to fix retail prices with other herbicide manufacturers.

In August 1985, Monsanto purchased G. D. Searle, the "NutraSweet" firm. NutraSweet, an artificial sweetener, had generated $700 million in sales that year, and Searle could offer Monsanto an experienced marketing and a sales staff as well as real profit potential — not to mention the fact that Searle's CEO Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was well-connected among a cabal of corrupt politicians in Washington DC. Since the late 1970s the company had sold nearly 60 low-margin businesses and, with two important agriculture product patents expiring in 1988, a major new cash source was more than welcome. What Monsanto didn't count on, however, was the controversy surrounding Searle's intrauterine birth control device called the Copper-7.

Soon after the acquisition, disclosures about hundreds of lawsuits over Searle's IUD surfaced and turned Monsanto's takeover into a public relations disaster. The disclosures, which inevitably led to comparisons with those about A. H. Robins, the Dalkan Shield manufacturer that eventually declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy, raised questions as to how carefully Monsanto management had considered the acquisition. In early 1986 Searle discontinued IUD sales in the United States. By 1988 Monsanto's new subsidiary faced an estimated 500 lawsuits against the Copper-7 IUD. As the parent company, Monsanto was well insulated from its subsidiary's liabilities by the legal "corporate veil".

Toward the end of the 1980s, Monsanto faced continued challenges from a variety of sources, including government and public concern over hazardous wastes, fuel and feedstock costs, and import competition. At the end of the 99th Congress, then President Ronald Reagan signed a $8.5 billion, five-year cleanup superfund reauthorization act. Built into the financing was a surcharge on the chemical industry created through the tax reform bill. Biotechnology regulations were just being formulated, and Monsanto, which already had types of genetically engineered bacteria ready for testing, was poised to be an active participant in the GMO biotech field.

In keeping with its strategy to become a leader in the health field, Monsanto and the Washington University Medical School entered into a five-year research contract in 1984. Two-thirds of the research was to be directed into areas with obviously commercial applications, while one-third of the research was to be devoted to theoretical work. One particularly promising discovery involved the application of the bovine growth factor, MARKETED as a way to greatly increase milk production.

In the burgeoning low-calorie sweetener market, challengers to NutraSweet were putting pressure on Monsanto. Pfizer Inc., a pharmaceutical company, was preparing to market its product, called alitame, which it claimed was far sweeter than NutraSweet and better suited for baking.

In an interview with Business Week, senior vice-president for research and development Howard Schneiderman commented, "To maintain our markets — and not become another steel industry — we must spend on research and development." Monsanto, which has committed 8% of its operating budget to research and development, far above the industry average, hoped to emerge in the 1990s as one of the leaders in the fields of biotechnology and pharmaceuticals that are only now emerging from their nascent stage.

By the end of the 1980s, Monsanto had restructured itself and become a producer of specialty chemicals, with a focus on biotechnology products. Monsanto enjoyed consecutive record years in 1988 and 1989 — sales were $8.3 billion and $8.7 billion, respectively. In 1988 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Cytotec, a drug that prevents gastric ulcers in high-risk cases. Sales of Cytotec in the United States reached $39 million in 1989.

The Monsanto Chemical Co. unit prospered with products like Saflex, a type of nylon carpet fiber. The NutraSweet Company held its own in 1989, contributing $180 million in earnings, with growth in the carbonated beverage segment (which Monsanto originated from since 1901 seed money from Coca-Cola to produce carcinogenic Saccharin). Almost 500 new products containing NutraSweet were introduced in 1989, for a total of 3,000 products.

Monsanto continued to invest heavily in research and development, with 7% of sales allotted for R&D. The investment began to pay off when the research and development department developed an all-natural fat substitute called Simplesse. The FDA declared in early 1990 that the Simplesse product was "generally recognized as safe" (GRAS) for use in frozen desserts. That year, the NutraSweet Company introduced Simple Pleasures frozen dairy dessert. Monsanto hoped to see Simplesse used eventually in salad dressings, yogurt, and mayonnaise.

Despite these successes, Monsanto remained frustrated by delays in obtaining FDA approval for bovine somatotropin (BST), a hormore chemical MARKETED to increase milk production in cows that causes mastitis (pus milk). Opponents to BST said it would upset the balance of supply and demand for milk, but Monsanto countered that BST would provide high-quality food supplies to consumers worldwide.

The final year of the 1980s also marked Monsanto's listing for the first time on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Monsanto officials expected the listing to improve opportunities for licensing and joint venture agreements.

Monsanto's Early 1990s Transitional Period

Monsanto had expected to celebrate 1990 as its 5th consecutive year of increased earnings, but numerous factors — the increased price of OIL due to the Persian Gulf War, a recession in key industries in the United States, and droughts in California and Europe — prevented Monsanto from achieving this goal. Net income was $546 million, a dramatic drop from the record of $679 the previous year. Nonetheless, subsidiary Searle, which had experienced considerable public relations scandals and headaches in the 1980s, had a record financial year in 1990. The subsidiary had established itself in the global pharmaceutical market and was beginning to emerge as an industry leader. The Monsanto Chemical Co., meanwhile, was a $4 billion business that made up the largest percentage of Monsanto's sales.

Monsanto continued to work at upholding hypocritical "The Monsanto Pledge", a 1988 declaration to reduce emissions of toxic substances. By its own estimates, Monsanto devoted $285 million annually to environmental expenditures. Furthermore, Monsanto and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) agreed to a cleanup program at Monsanto's detergent and phosphate plant in Richmond County, Georgia.

Monsanto restructured during the early 1990s to help cut losses during a difficult economic time. Net income in 1991 was only $296 million, $250 million less than the previous year. Despite this showing, 1991 was a good year for some of Monsanto's newest products. Bovine somatotropin finally gained FDA approval and was sold in Mexico and Brazil, and Monsanto received the go-ahead to use the fat substitute, Simplesse, in a full range of food products, including yogurt, cheese and cheese spreads, and other low-fat spreads. In addition, the herbicide Dimension was approved in 1991, and scientists at Monsanto controversially tested genetically engineered (GE or GMO) plants in field trials.

Furthermore, Monsanto expanded internationally, opening an office in Shanghai and a plant in Beijing, China. Monsanto also hoped to expand in Thailand, and entered into a joint venture in Japan with Mitsubishi Chemical Co.

Monsanto's sales in 1992 hit $7.8 million. However, as net income dropped 130% from 1991 due to several one-time aftertax charges, Monsanto prepared itself for challenging times. The patent on NutraSweet brand sweetener expired in 1992, and in preparation for increased competition, Monsanto launched new products, such as the NutraSweet Spoonful, which came in tabletop serving jars, like sugar. Monsanto also devoted ongoing research and development to Sweetener 2000, a high-intensity product.

In 1992, Monsanto denied that it planned to sell G. D. Searle and Co., pointing out that Searle was a profitable subsidiary that launched many new products. However, to decrease losses, Monsanto did sell Fisher Controls International Inc., a subsidiary that manufactures process control equipment. Profits from the sale were used to buy the Ortho lawn-and-garden business from Chevron Chemical Co.

Monsanto Reinvents Itself in the 1990s

Monsanto expected to see growth in its agricultural, chemical, and biotechnological divisions. In 1993, Monsanto and NTGargiulo joined forces to produce a (GMO) genetically altered tomato. As the decade progressed, biotechnology played an increasingly important role, eventually emerging as the focal point of Monsanto's operations. The foray into biotechnology, begun in the mid-1980s with a $150-million investment in a genetic engineering lab in Chesterfield, Missouri, had been faithfully supported by further investments in the ensuing years. Monsanto's efforts finally yielded tangible success in 1993, when BST was approved for commercial sale after a frustratingly slow FDA approval process. In the coming years, the development of further biotech products moved to the forefront of Monsanto's activities, ushering in a period of profound change. Fittingly, the sweeping, strategic alterations to Monsanto's focus were preceded by a change in leadership, making the last decade of the 20th century one of the most dynamic eras in Monsanto's history.

Toward the end of 1994, Mahoney announced his retirement, effective the following year in March 1995. As part of the same announcement, Mahoney revealed that Robert B. Shapiro, Monsanto's president and chief operating officer, would be elected by Monsanto's board of directors as his successor. Shapiro, who had joined Searle in 1979 before being named executive vice-president of Monsanto in 1990, did not waver from exerting his influence over the company he now found himself presiding over. At the time of his promotion, Shapiro inherited a company that ranked as the largest domestic ACRYLIC manufacturer in the world, generating $3 billion of its $7.9 billion in total revenues from chemical-related sales. This dominant side of Monsanto's business, representing the foundation upon which it had been built, was eliminated under Shapiro's stewardship, replaced by a resolute commitment to biotech.

Between the mid-1980s and the mid-1990s, Monsanto had spent approximately $1 billion on developing its biotech business. Although biotech was regarded as a commercially unproven market by some industry analysts, Shapiro pressed forward with the research and development of biotech products, and by the beginning of 1996 he was ready to launch Monsanto's first biotech product line. Monsanto began marketing herbicide-tolerant GMO soybeans, genetically engineered to resist Monsanto's PATENTED Roundup herbicide, and insect-resistant GMO BT cotton, beginning with 2,000,000 acres of both crops. By the fall of 1996, there were early indications that the first harvests of genetically engineered crops were performing better than expected (yet WORSE results than traditional and organic crops). News of the encouraging results prompted Shapiro to make a startling announcement in October 1996, when he revealed that Monsanto was considering divesting its chemical business as part of a major reorganization into a life-sciences company.

By the end of 1996, when Shapiro announced he would spin-off the chemical operations as a separate company, Monsanto faced a future without its core business, a $3 billion contributor to Monsanto's annual revenue volume. Without the chemical operations, Monsanto would be reduced to an approximately $5-billion company deriving half its sales from agricultural products and the rest from pharmaceuticals and food ingredients, but Shapiro did not intend to leave it as such. He foresaw an aggressive push into biotech products, a move that industry pundits generally perceived as astute. "It would be a gamble if they didn't do it," commented one analyst in reference to the proposed divestiture. "Monsanto is trying to transform itself into a high-growth agricultural and life sciences company. Low-growth cyclical chemical operations do not fit that bill." Spurring Shapiro toward this sweeping reinvention of Monsanto were enticing forecasts for the market growth of plant biotech products. A $450 million business in 1995, the market for plant biotech products was expected to reach $2 billion by 2000 and $6 billion by 2005. Shapiro wanted to dominate this fast-growing market as it matured by shaping Monsanto into what he described as the main provider of "Agricultural Biotechnology".

As preparations were underway for the spin-off of Monsanto's chemical operations into a new, publicly owned company named Solutia Inc., Shapiro was busy filling the void created by the departure of Monsanto's core business. A flurry of acquisitions completed between 1995-1997 greatly increased Monsanto's presence in life sciences, quickly compensating for the revenue lost from the spin-off of Solutia. Among the largest acquisitions were Calgene, Inc., a leader in plant biotech, which was acquired in a two-part transaction in 1995 and 1997, and a 40% interest in Dekalb Genetics Corp., the second-largest seed-corn company in the United States. In 1998, Monsanto acquired the rest of DeKalb, paying $2.3 billion for the Illinois-based company.

By the end of the 1990s, Monsanto bore only partial resemblance to the Monsanto company that entered the decade. The acquisition campaign that added dozens of biotechnology companies to its portfolio had created a new, dominant force in the promising life sciences field, placing Monsanto in a position to reap massive rewards in the years ahead. For example, a rootworm-resistant strain under development had the potential to save $1 billion worth of damages to corn crops per year. Monsanto's pharmaceutical business also faced a promising future, highlighted by the introduction of a new arthritis medication named Celebrex in 1999. During its first year, Celebrex registered a record number of prescriptions. As Monsanto entered the 21st century, however, there were two uncertainties that loomed as potentially serious obstacles blocking its future success. The acquisition campaign of the mid- and late-1990s had greatly increased Monsanto's debt, forcing Monsanto to desperately search for cash. Secondly, there was growing opposition to genetically altered crops at the decade's conclusion, prompting the United Kingdom to ban the yields from GMO crops for a year. A great part of Monsanto's future success depended on the resolution of these two issues.

Monsanto's Financial History & Corporate Instability

Monsanto had a difficult time during 2002. Its share price had been steadily falling and, in spite of an upturn in sales in the fourth quarter, total sales for 2002 were only $4,673m, compared to $5,462m for 2001. The primary causes, according to the company, were lower volumes of RoundUp sales in the U.S. due to drought, lower prices for RoundUp due to it going off-patent and facing increased competition from competitors, and lower sales of RoundUp and seeds in Latin America.

Events in Argentina also affected the company in other ways: Monsanto's Argentine unit lost $154 million in the 2002 fiscal year, due to the collapse of the Argentine economy and a deepening recession which forced the government to default on most of its public debt, and devalue the peso in January 2002. The government also converted what was a dollar economy into a peso economy and, as a result, Monsanto received devalued pesos for products it had sold in dollars, slashing its sales income.

In December 2002, CEO Hendrik Verfaillie resigned after he and the board agreed that his performance had been disappointing and the company had faced extensive criticism for failing to deal more honestly and effectively with its difficulties. 'This is a company that has been optimistic on the borderline of lying,' said Sergey Vasnetsov, senior analyst with Lehman Brothers in New York. 'Monsanto has been feeding us these fantasies for two years, and when we saw they weren't real,' its stock price fell.

In 2009, Monsanto profited about $2 billion. After much controversy... in 2010, Monsanto profits dove 50% to about $1 billion. GMO crops are massively failing, some even seedless at harvest time. Subsidized crops are LOSING MONEY annually. The USDA is calling it a "yield-drag" but we all know the GMOs do NOT outperform organic crops... unless you're an accountant for Monsanto.

No matter what weaknesses Monsanto has, it is worth bearing in mind the following: Global sales of Roundup herbicide exceed those of the next 6 leading herbicides combined. Monsanto holds the #1 or #2 position in key corn and soybean markets in North America, Latin America, and Asia. Monsanto also holds a leading position in the European wheat market. Monsanto is the world leader in biotechnology crops. Seeds with Monsanto traits accounted for more than 90% of the acres planted worldwide with herbicide-tolerant or insect-resistant traits in 2001.

Timeline of Monsanto's Dark History

1901: Monsanto was founded in St. Louis, Missouri by John Francis Queeny, a 30-year veteran of the pharmaceutical industry. Queeny funded the start-up with capital from Coca-Cola (saccharin). Founder John Francis Queeny named Monsanto Chemical Works after his wife, Olga Mendez Monsanto. Queeny's father in law was Emmanuel Mendes de Monsanto, wealthy financier of a sugar company active in Vieques, Puerto Rico and based in St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies.

1902: Monsanto manufactures its first product, the artificial sweetener Saccharin, which Monsanto sold to the Coca-Cola Company. The U.S. government later files suit over the safety of Saccharin — but loses.

1904: Queeny persuaded family and friends to invest $15000, Monsanto has strong ties to The Walt Disney Company, it having financial backing from the Order's Bank of America founded in Jesuit-ruled San Francisco by Italian-American Roman-Catholic Knight of Malta Amadeo Giannini.

1905: Monsanto company was also producing caffeine and vanillin and was beginning to turn a profit.

1906: The government's monopoly on meat regulation began, when in response to public panic resulting from the publication of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, Teddy Roosevelt signed legislation mandating federal meat inspections. Today, Salatin claims that agricultural regulation favors multinational corporations such as ConAgra and Monsanto because the treasonous science that supports the USDA regulatory framework is paid for by these corporations, which continue to give large grants to leading schools and research facilities.

1908: John Francis Queeny leaves his part-time job as the new branch manager of another drug house the Powers-Weightman-Rosegarten Company to become Monsanto's full-time president.

1912: Agriculture again came to the forefront with the creation of the DeKalb County Farm Bureau, one of the first organizations of its kind. In the 1930s the DeKalb AgResearch Corporation (today MONSANTO) marketed its first hybrid seed corn.

1914-1918: During WWI, cut off from imported European chemicals, Monsanto was forced to manufacture it's own, and it's position as a leading force in the chemical industry was assured. Unable to import foreign supplies from Europe during World War I, Queeny turned to manufacturing his own raw materials. It was then his scientists discovered that the Germans, in anticipation of the war, had ripped out vital pages from their research books which explained various chemical processes.

1915: Business expanded rapidly. Monsanto sales surpass the $1,000,000 mark for the first time.

1917: U.S. government sues Monsanto over the safety of Monsanto's original product, saccharin. Monsanto eventually won, after several years in court.

1917: Monsanto added more and more products: vanillin, caffeine, and drugs used as sedatives and laxatives.

1917: Bayer, The German competition cut prices in an effort to drive Monsanto out of business, but failed. Soon, Monsanto diversified into phenol (a World War I -era antiseptic), and aspirin when Bayer's German patent expired in 1917. Monsanto began making aspirin, and soon became the largest manufacturer world-wide.

1918: With the purchase of an Illinois acid company, Monsanto began to widen the scope of its factory operations.

Mar 15, 1918: More than 500 of the 750 employees of the Monsanto Chemical Works, which has big contracts for the Government, went on strike, forcing the plant to dose down.

Aug 15, 1919: Thereafter much of it was declared surplus, and a contract was entered into with the Monsanto Chemical Co., of St. Louis, Mo., by which contract the Director of Sales authorized the Monsanto Co. to sell for the United States its surplus phenol, estimated at 27521242 pounds, for a market price to be fixed from time to time by the representative of the contracting officer of the United States, but with a minimum price of 9 cents a pound.

1919: Monsanto established its presence in Europe by entering into a partnership with Graesser's Chemical Works at Cefn Mawr near Ruabon, Wales to produce vanillin, salicylic acid, aspirin and later rubber.

1920s: In its third decade, Monsanto expanded into basic industrial chemicals like sulfuric acid and other chemicals.

Jan 5, 1920: The petitioner was authorized to sell two tracts of land in the Common Fields of Cahokia, St. Clair County, containing 2.403 acres and 3.46 acres respectively, to the Monsanto Chemical Works for the sum of $1500.

1920-1921: A postwar depression during the early 1920s affected profits, but by the time John Queeny turned over Monsanto to Edgar in 1928 the financial situation was much brighter.

1926: Environmental policy was generally governed by local governments, Monsanto Chemical Company founded and incorporated the town of Monsanto, later renamed Sauget, Illinois, to provide a more business friendly environment for one of its chemical plants. For years, the Monsanto plant in Sauget was the nation's largest producer of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). And although polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were banned in the 1970s, they remain in the water along Dead Creek in Sauget.

1927: Monsanto had over 2,000 employees, with offices across the country and in England.

1927: Shortly after its initial listing on the New York Stock Exchange, Monsanto moved to acquire 2 chemical companies that specialized in rubber. Other chemicals were added in later years, including detergents.

1928: John Queeny's son Edgar Monsanto Queeny takes over the Monsanto company. Monsanto had gone public, a move that paved the way for future expansion. At this time, Monsanto had 55 shareholders, 1,000 employees, and owned a small company in Britain.

1929: Monsanto acquires Rubber Services Laboratories. Charlie Sommer joined Monsanto, and later became president of Monsanto in 1960.

October 1929: The folks at Monsanto Co. fished through their records, but they couldn't find out why the company's symbol is MTC. Monsanto went public in October 1929, just a few days before the great stock market crash. Some symbols are holdovers from the 19th century, when telegraph operators used single-letter symbols for the most active stocks to conserve wire space, says the New York Stock Exchange. Mergers, acquisitions and failure have caused many single-letter symbols to change

1929: Monsanto began production of PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) in the United States. PCBs were considered an industrial wonder chemical — an oil that would not burn, was impervious to degradation and had almost limitless applications. Today PCBs are considered one of the gravest chemical threats on the planet. PCBs, widely used as lubricants, hydraulic fluids, cutting oils, waterproof coatings and liquid sealants, are potent carcinogens and have been implicated in reproductive, developmental and immune system disorders. The world's center of PCB manufacturing was Monsanto's plant on the outskirts of East St. Louis, Illinois, which has the highest rate of fetal death and immature births in the state.

Monsanto produced PCBs for over 50 years and they are now virtually omnipresent in the blood and tissues of humans and wildlife around the globe — from the polar bears at the north pole to the penguins in Antarctica. These days PCBs are banned from production and some experts say there should be no acceptable level of PCBs allowed in the environment. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says, "PCB has been demonstrated to cause cancer, as well as a variety of other adverse health effects on the immune system, reproductive system, nervous system and endocrine system." But the evidence of widespread contamination from PCBs and related chemicals has been accumulating from 1965 onwards and internal company papers show that Monsanto knew about the PCB dangers from early on.

The PCB problem was particularly severe in the town of Anniston in Alabama where discharges from the local Monsanto plant meant residents developed PCB levels hundreds or thousands of times the average. As The Washington Post reported, "for nearly 40 years, while producing the now-banned industrial coolants known as PCBs at a local factory, Monsanto Co. routinely discharged toxic waste into a west Anniston creek and dumped millions of pounds of PCBs into oozing open-pit landfills. And thousands of pages of Monsanto documents : many emblazoned with warnings such as 'CONFIDENTIAL: Read and Destroy' : show that for decades, the corporate giant concealed what it did and what it knew."

Ken Cook of the Environmental Working Group says that based on the Monsanto documents made public, Monsanto "knew the truth from the very beginning. They lied about it. They hid the truth from their neighbors." One Monsanto memo explains their justification: "We can't afford to lose one dollar of business." Eventually Monsanto was found guilty of conduct "so outrageous in character and extreme in degree as to go beyond all possible bounds of decency so as to be regarded as atrocious and utterly intolerable in civilized society".

1930s: DeKalb AgResearch Corporation (today MONSANTO) marketed its first **HYBRID** seed corn (maize).

1933: Incorporated as Monsanto Chemical Company

1934: "I recognized my two selves: a crusading idealist and a cold, granitic believer in the law of the jungle" — Edgar Monsanto Queeny, Monsanto chairman, 1943-63, "The Spirit of Enterprise"

1935: Edward O'Neal (who became chairperson in 1964) came to Monsanto with the acquisition of the Swann Corporation. Monsanto goes into the soap and detergents industry, starts producing phosphorus.

1938: Monsanto goes into the plastic business (the year after DuPont helped ban hemp because it was superior to their new NYLON product made from Rockefeller OIL). Monsanto became involved in plastics when it completely took over Fiberloid, one of the oldest nitrocellulose production companies, which had a 50% stake in Shawinigan Resins.

1939: Monsanto purchased Resinox, a subsidiary of Corn Products, and Commercial Solvents, which specialized in phenolic resins. Thus, just before the war, Monsanto's plastics interests included phenol-formaldehyde thermosetting resins, cellulose and vinyl plastics.

1939-1945: Monsanto conducts research on uranium for the Manhattan Project in Dayton, Ohio. Dr. Charles Thomas, who later served as Monsanto's chairman of the board, was present at the first test explosion of the atomic bomb. During World War II, Monsanto played a significant role in the Manhattan Project to develop the atom bomb. Monsanto operated the Dayton Project, and later Mound Laboratories in Miamisburg, Ohio, for the Manhattan Project, the development of the first nuclear weapons and, after 1947, the Atomic Energy Commission.

1940s: Monsanto had begun focusing on plastics and synthetic fabrics like polystyrene (still widely used in food packaging and other consumer products), which is ranked 5th in the EPA's 1980s listing of chemicals whose production generates the most total hazardous waste. From the 1940s onwards Monsanto was one of the top 10 US chemical companies.

1941: By the time the United States entered World War II, the domestic chemical industry had attained far greater independence from Europe. Monsanto, strengthened by its several acquisitions, was also prepared to produce such strategic materials as phosphates and inorganic chemicals. Most important was Monsanto's acquisition of a research and development laboratory called Thomas and Hochwalt. The well-known Dayton, Ohio, firm strengthened Monsanto at the time and provided the basis for some of its future achievements in chemical technology. One of its most important discoveries was styrene monomer, a key ingredient in synthetic rubber and a crucial product for the armed forces during the war. Edward J. Bock joined Monsanto in 1941 as an engineer — he rose through the ranks to become a member of the board of directors in 1965 and president in 1968.

1943: Massive Texas City plant starts producing synthetic rubber for the Allies in World War II.

1944: Monsanto began manufacturing DDT, along with some 15 other companies. The use of DDT in the U.S. was banned by Congress in 1972.

1945: Following WW2, Monsanto championed the use of chemical pesticides in agriculture, and began manufacturing the herbicide 2,4,5-T, which contains dioxin. Monsanto has been accused of covering up or failing to report dioxin contamination in a wide range of its products.

1949: Monsanto acquired American Viscose from England's Courtauld family.

1950: Monsanto began to produce urethane foam — which was flexible, easy to use, and later became crucial in making automobile interiors.

1953: Toxicity tests on the effects of 2 PCBs showed that more than 50% of the rats subjected to them DIED, and ALL of them showed damage.

1954: Monsanto partnered with German chemical giant Bayer to form Mobay and market polyurethanes in the USA.

1955: Monsanto acquired Lion Oil refinery, increasing its assets by more than 50%. Stockholders during this time numbered 43,000. Monsanto starts producing petroleum-based fertilizer.

1957: Monsanto moved to the suburban community of Creve Coeur, having finally outgrown its headquarters in downtown St. Louis, Missouri.

1957-1967: Monsanto was the creator of several attractions in Disney's Tommorrowland. Often they revolved around the the virtues of chemicals and plastics. Their "House of the Future" was constructed entirely of plastic, but it was NOT biodegradable. "After attracting a total of 20 million visitors from 1957 to 1967, Disney finally tore the house down, but discovered it would not go down without a fight. According to Monsanto Magazine, wrecking balls literally bounced off the glass-fiber, reinforced polyester material. Torches, jackhammers, chain saws and shovels did not work. Finally, choker cables were used to squeeze off parts of the house bit by bit to be trucked away."

1959: Monsanto sets up Monsanto Electronics Co. in Palo Alto, begins producing ultra-pure silicon for the high-tech industry, in an area which would later become a Superfund site.

1960: Edgar Queeny turned over the chair of Monsanto to Charles Thomas, one of the founders of the research and development laboratory so important to Monsanto. Charlie Sommer, who had joined Monsanto in 1929, became president. According to Monsanto historian Dan Forrestal, "Leadership during the 1960s and early 1970s came principally from ... executives whose Monsanto roots ran deep." Under their combined leadership Monsanto saw several important developments, including the establishment of the Agricultural Chemicals division with focus on herbicides, created to consolidate Monsanto's diverse agrichemical product lines.

1961-1971: Agent Orange was a mixture of 2,4,5-T and 2,4-D and had very high concentrations of dioxin. Agent Orange was by far the most widely used of the so-called "Rainbow Herbicides" employed in the Herbicidal Warfare program as a defoliant during the Vietnam War. Monsanto became one of 10-36 producers of Agent Orange for US Military operations in Vietnam. Dow Chemical and Monsanto were the two largest producers of Agent Orange for the U.S. military. The Agent Orange produced by Monsanto had dioxin levels many times higher than that produced by Dow Chemicals, the other major supplier of Agent Orange to Vietnam. This made Monsanto the key defendant in the lawsuit brought by Vietnam War veterans in the United States, who faced an array of debilitating symptoms attributable to Agent Orange exposure. Agent Orange is later linked to various health problems, including cancer. U.S. Vietnam War veterans have suffered from a host of debilitating symptoms attributable to Agent Orange exposure. Agent Orange contaminated more than 3,000,000 civilians and servicemen. According to Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 4.8 million Vietnamese people were exposed to Agent Orange, resulting in 400,000 deaths and disabilities, plus 500,000 children born with birth defects, leading to calls for Monsanto to be prosecuted for war crimes. Internal Monsanto memos show that Monsanto knew of the problems of dioxin contamination of Agent Orange when it sold it to the U.S. government for use in Vietnam. Look at what the "EFFECTS" of Agent Orange look like... keep in mind it was used to remove leaves from the trees where AMERICAN SOLDIERS were breathing, eating, sleeping.

1962: Public concern over the environment began to escalate. Ralph Nader's activities and Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring had been influential in increasing the U.S. public's awareness of activities within the chemical industry in the 1960s, and Monsanto responded in several ways to the pressure.

1962: Monsanto's European expansion continued, with Brussels becoming the permanent overseas headquarters.

1964: Monsanto changed its name to Monsanto Company in acknowledgment of its diverse product line. The company consisted of 8 divisions, including petroleum, fibers, building materials, and packaging. Edward O'Neal became chairperson (came to Monsanto in 1935 with the acquisition of the Swann Corporation) was the first chair in Monsanto history who had not first held the post of president.

1964: Monsanto introduced "biodegradable" detergents.

1965: While working on an ulcer drug in December, James M. Schlatter, a chemist at G.D. Searle & Company, accidentally discovers aspartame, a substance that is 180x sweeter than sugar yet has no calories.

1965: AstroTurf (fake grass) was co-invented by Donald L. Elbert, James M. Faria, and Robert T. Wright, employees of Monsanto Company. It was patented in 1967 and originally sold under the name "Chemgrass". It was renamed AstroTurf by Monsanto employee John A. Wortmann after its first well-publicized use at the Houston Astrodome stadium in 1966.

1965: The evidence of widespread contamination from PCBs and related chemicals has been accumulating and internal Monsanto papers show that Monsanto knew about the PCB dangers from early on.

1967: Monsanto entered into a joint venture with IG Farben = the German chemical firm that was the financial core of the Hitler regime, and was the main supplier of Zyklon-B gas to the German government during the extermination phase of the Holocaust; IG Farben was not dissolved until 2003.

1967: Searle began the safety tests on aspartame that were necessary for applying for FDA approval of food additives. Dr. Harold Waisman, a biochemist at the University of Wisconsin, conducts aspartame safety tests on infant monkeys on behalf of the Searle Company. Of the 7 monkeys that were being fed aspartame mixed with milk, 1 monkey DIED and 5 other monkeys had grand mal seizures.

1968: Edgar Queeny dies, leaving no heirs. Edward J. Bock (who had joined Monsanto in 1941 as an engineer) become a member of the board of directors in 1965, and became president of Monsanto in 1968.

1968: With experts at Monsanto in no doubt that Monsanto's PCBs were responsible for contamination, Monsanto set up a committee to assess its options. In a paper distributed to only 12 people but which surfaced at the trial in 2002, Monsanto admitted "that the evidence proving the persistence of these compounds and their universal presence as residues in the environment is beyond question ... the public and legal pressures to eliminate them to prevent global contamination are inevitable". Monsanto papers seen by The Guardian newspaper reveal near panic. "The subject is snowballing. Where do we go from here? The alternatives: go out of business; sell the hell out of them as long as we can and do nothing else; try to stay in business; have alternative products", wrote the recipient of one paper.

1968: Monsanto became the first organization to mass-produce visible LEDs, using gallium arsenide phosphide to produce red LEDs suitable for indicators. Light Emitting Diodes (LEDs) ushered in the era of solid-state lights. From 1968 to 1970, sales doubled every few months. Their products (discrete LEDs and seven-segment numeric displays) became the standards of industry. The primary markets then were electronic calculators, digital watches, and digital clocks.

1969: High overhead costs and a sluggish national economy led to a dramatic 29% decrease in earnings.

1969: Monsanto wrote a confidential Pollution Abatement Plan which admitted that "the problem involves the entire United States, Canada and sections of Europe, especially the UK and Sweden".

1969: Monsanto produces Lasso herbicide, better known as Agent Orange, which was used as defoliant by the U.S. Government during the Vietnam War. "[Lasso's] success turns around the struggling Agriculture Division," Monsanto's web page reads.

1970s: Monsanto was a pioneer of optoelectronics in the 1970s. Although Bock had a reputation for being a committed Monsanto executive, several factors contributed to his volatile term as president. Sales were up in 1970, but Bock's implementation of the 1971 reorganization caused a significant amount of friction among members of the board and senior management. In spite of the fact that this move, in which Monsanto separated the management of raw materials from Monsanto's subsidiaries, was widely praised by security analysts, Bock resigned from the presidency in February 1972.

1970: Cyclamate (the reigning low-calorie artificial sweetener) is pulled off the market in November after some scientists associate it with cancer. Questions are also raised about safety of saccharin, the only other artificial sweetener on the market, leaving the field wide open for aspartame.

December 18, 1970: Searle Company executives lay out a "Food and Drug Sweetener Strategy" that they feel will put the FDA into a positive frame of mind about aspartame. An internal policy memo describes psychological tactics Monsanto should use to bring the FDA into a subconscious spirit of participation" with them on aspartame and get FDA regulators into the "habit of saying Yes."

1971: Neuroscientist Dr. John Olney (whose pioneering work with monosodium glutamate MSG was responsible for having it removed from baby foods) informs Searle that his studies show that aspartic acid (one of the ingredients of aspartame) caused holes in the brains of infant mice. One of Searle's own researchers confirmed Dr. Olney's findings in a similar study.

1972: The use of DDT was banned by U.S. Congress, due in large part to efforts by environmentalists, who persisted in the challenge put forth by Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring in 1962, which sought to inform the public of the side effects associated with the insecticide, which had been much-welcomed in the fight against malaria-transmitting mosquitoes.

1973: Monsanto developed and patented the glyphosate molecule in the 1970s. Monsanto began manufacturing the herbicide Roundup, which has been marketed as a "safe", general-purpose herbicide for widespread commercial and consumer use, even though its key ingredient, glyphosate, is a highly toxic poison for animals and humans.

1973: After spending tens of millions of dollars conducting safety tests, the G.D. Searle Company applies for FDA approval and submits over 100 studies they claim support aspartame's safety. One of the first FDA scientists to review the aspartame safety data states that "the information provided (by Searle) is inadequate to permit an evaluation of the potential toxicity of aspartame". She says in her report that in order to be certain that aspartame is safe, further clinical tests are needed.

1974: Attorney Jim Turner (consumer advocate who was instrumental in getting cyclamate taken off the market) meets with Searle representatives in May to discuss Dr. Olney's 1971 study which showed that aspartic acid caused holes in the brains of infant mice.

1974: The FDA grants aspartame its first approval for restricted use in dry foods on July 26.

1974: Jim Turner and Dr. John Olney file the first objections against aspartame's approval in August.

1975: After a 9-month search, John W. Hanley, a former executive with Procter & Gamble, was chosen as president. Hanley also took over as chairperson.

1976: The success of the herbicide Lasso had turned around Monsanto's struggling Agriculture Division, and by the time Agent Orange was banned in the U.S. and Lasso was facing increasing criticism, Monsanto had developed the weedkiller "Roundup" (active ingredient: glyphosate) as a replacement. Launched in 1976, Roundup helped make Monsanto the world's largest producer of herbicides. RoundUp was commercialized, and became the world's top-selling herbicide. Within a few years of its 1976 launch, Roundup was being marketed in 115 countries.

The success of Roundup coincided with the recognition by Monsanto executives that they needed to radically transform a company increasingly under threat. According to a recent paper by Dominic Glover, "Monsanto had acquired a particularly unenviable reputation in this regard, as a major producer of both dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) — both persistent environmental pollutants posing serious risks to the environment and human health. Law suits and environmental clean-up costs began to cut into Monsanto's bottom line, but more seriously there was a real fear that a serious lapse could potentially bankrupt the company." According to Glover, Roundup "Sales grew by 20% in 1981 and as the company increased production it was soon Monsanto's most profitable product (Monsanto 1981, 1983)... It soon became the single most important product of Monsanto's agriculture division, which contributed about 20% of sales and around 45% of operating income to the company's balance sheet each year during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Today, glyphosate remains the world's biggest herbicide by volume of sales."

1976: Monsanto produces Cycle-Safe, the world's first plastic soft-drink bottle. The bottle, suspected of posing a cancer risk, is banned the following year by the Food and Drug Administration.

1976: Turner & Olney's petition on March 24 triggers an FDA investigation of the laboratory practices of aspartame's manufacturer, G.D. Searle. The investigation finds Searle's testing procedures shoddy, full of inaccuracies and "manipulated" test data. The investigators report they "had never seen anything as bad as Searle's testing."

January 10, 1977: The FDA formally requests the U.S. Attorney's office to begin grand jury proceedings to investigate whether indictments should be filed against Searle for knowingly misrepresenting findings and "concealing material facts and making false statements" in aspartame safety tests. This is the first time in the FDA's history that they request a criminal investigation of a manufacturer.

January 26, 1977: While the grand jury probe is underway, Sidley & Austin, the law firm representing Searle, begins job negotiations with the U.S. Attorney in charge of the investigation, Samuel Skinner.

March 8, 1977: G. D. Searle hires prominent Washington insider Donald Rumsfeld as the new CEO to try to turn the beleaguered company around. A former Member of Congress and Secretary of Defense in the Ford Administration, Rumsfeld brings in several of his Washington cronies as top management. Donald Rumsfeld followed Searle as CEO, and then as President of Searle from 1977-1985.

July 1, 1977: Samuel Skinner leaves the U.S. Attorney's office on July 1st and takes a job with Searle's law firm. (see Jan. 26th)

August 1, 1977: The Bressler Report, compiled by FDA investigators and headed by Jerome Bressler, is released. The report finds that 98 of the 196 animals died during one of Searle's studies and weren't autopsied until later dates, in some cases over one year after death. Many other errors and inconsistencies are noted. For example, a rat was reported alive, then dead, then alive, then dead again; a mass, a uterine polyp, and ovarian neoplasms were found in animals but not reported or diagnosed in Searle's reports.

December 8, 1977: U.S. Attorney Skinner's withdrawal and resignation stalls the Searle grand jury investigation for so long that the statue of limitations on the aspartame charges runs out. The grand jury investigation is dropped. (borderline treason)

1979: The FDA established a Public Board of Inquiry (PBOI) in June to rule on safety issues surrounding NutraSweet.

1980: September 30, FDA Board of Inquiry comprised of 3 independent scientists, confirmed that aspartame "might induce brain tumors". The Public Board of Inquiry concludes NutraSweet should not be approved pending further investigations of brain tumors in animals. The board states it "has NOT been presented with proof of reasonable certainty that aspartame is safe for use as a food additive." The FDA had actually banned aspartame based on this finding, only to have Searle Chairman Donald Rumsfeld (Ford's Secretary of Defense 1975-1977, Bush's Secretary of Defense 2001-2006) vow to "call in his markers," to get it approved in 1981.

1980: Monsanto established the Edgar Monsanto Queeny safety award in honor of its former CEO (1928-1960), to encourage accident prevention.

January 1981: Donald Rumsfeld, CEO of Searle, states in a sales meeting that he is going to make a big push to get aspartame approved within the year. Rumsfeld says he will use his political pull in Washington, rather than scientific means, to make sure it gets approved.

May 19, 1981: 3 of 6 in-house FDA scientists who were responsible for reviewing the brain tumor issues, Dr. Robert Condon, Dr. Satya Dubey, and Dr. Douglas Park, advise against approval of NutraSweet, stating on the record that the Searle tests are unreliable and not adequate to determine the safety of aspartame.

1981: Ronald Reagan is sworn in as President of the United States. Reagan's transition team, which includes Donald Rumsfeld, CEO of G. D. Searle, hand picks Dr. Arthur Hull Hayes Jr. to be the new FDA Commissioner. On January 21, the day after Ronald Reagan's inauguration, GD Searle re-applied to the FDA for approval to use aspartame in food sweetener, and Reagan's new FDA commissioner, Arthur Hayes Hull, Jr., appointed a 5-person Scientific Commission to review the board of inquiry's decision. It soon became clear that the panel would uphold the ban by a 3-2 decision, but Hull then installed a 6th member on the commission, and the vote became deadlocked. He then personally broke the tie in aspartame's favor. Hull later left the FDA under allegations of impropriety, served briefly as Provost at New York Medical College, and then took a position with Burston-Marsteller, the chief public relations firm for both Monsanto and GD Searle. Since that time Hull has never spoken publicly about aspartame.

July 15, 1981: In one of his first official acts, Dr. Arthur Hayes Jr., the new FDA commissioner, overrules the Public Board of Inquiry, ignores the recommendations of his own internal FDA team and approves NutraSweet for dry products. Hayes says that aspartame has been shown to be safe for its' proposed uses and says few compounds have withstood such detailed testing and repeated close scrutiny. G.D. Searle gets FDA approval for aspartame (NutraSweet). Monsanto completes its acquisition of Searle in 1985.

1982: Monsanto GMO scientists genetically modify a plant cell for the first time!

1982: Some 2,000 people are relocated from Times Beach, Missouri, which was found to be so thoroughly contaminated with dioxin, a by-product of PCB manufacturing, that the government ordered it evacuated. Dioxins are endocrine and immune system disruptors, cause congenital birth defects, reproductive and developmental problems, and increase the incidence of cancer, heart disease and diabetes in laboratory animals. Critics say a St. Louis-area Monsanto chemical plant was a source but Monsanto denies any connection.

October 15, 1982: The FDA announces that GD Searle has filed a petition that aspartame be approved as a sweetener in carbonated beverages and other liquids.

July 1, 1983: The National Soft Drink Association (NSDA) urges the FDA to delay approval of aspartame for carbonated beverages pending further testing because aspartame is very unstable in liquid form. When liquid aspartame is stored in temperatures above 85°ree;F (degrees Fahrenheit), aspartame breaks down into known toxins Diketopiperazines (DKP), methyl (wood) alcohol, and formaldehyde.

July 8, 1983: The National Soft Drink Association drafts an objection to the final ruling which permits the use of aspartame in carbonated beverages and syrup bases and requests a hearing on the objections. The association says that Searle has not provided responsible certainty that aspartame and its' degradation products are safe for use in soft drinks.

August 8, 1983: Consumer Attorney, Jim Turner of the Community Nutrition Institute and Dr. Woodrow Monte, Arizona State University's Director of Food Science and Nutritional Laboratories, file suit with the FDA objecting to aspartame approval based on unresolved safety issues.

September, 1983: FDA Commissioner Hayes resigns under a cloud of controversy about his taking unauthorized rides aboard a General Foods jet. (General foods is a major customer of NutraSweet) Burson-Marsteller, Searle's public relation firm (which also represented several of NutraSweet's major users), immediately hires Hayes as senior scientific consultant.

Fall 1983: The first carbonated beverages containing aspartame are sold for public consumption.

1983: Diet Coke was sweetened with aspartame after the sweetener became available in the United States.

November 1984: Center for Disease Control (CDC) "Evaluation of consumer complaints related to aspartame use." (summary by B. Mullarkey)

1985: Monsanto purchased G.D. Searle, the chemical company that held the patent to aspartame, the active ingredient in NutraSweet. Monsanto was apparently untroubled by aspartame's clouded past, including a 1980 FDA Board of Inquiry, comprised of three independent scientists, which confirmed that it "might induce brain tumors". The aspartame business became a separate Monsanto subsidiary, the NutraSweet Company.

1986: Monsanto found guilty of negligently exposing a worker to benzene at its Chocolate Bayou Plant in Texas. It is forced to pay $100 million to the family of Wilbur Jack Skeen, a worker who died of leukemia after repeated exposures.

1986: At a congressional hearing, medical specialists denounce a National Cancer Institute study disputing that formaldehyde causes cancer. Monsanto and DuPont scientists helped with the study, whose author provided results to the Formaldehyde Institute industry representatives nearly six months before releasing the study to the EPA, labor unions, and the public.

1986: Monsanto spends $50,000 against California's anti-toxics initiative, Proposition 65. The initiative prohibits the discharge of chemicals known to cause cancer or birth defects into drinking water supplies.

1987: Monsanto conducted the first field tests of genetically engineered (GMO) crops.

1987: Monsanto is one of the companies named in an $180 million settlement for Vietnam War veterans exposed to Agent Orange.

1987: Monsanto consolidated its AstroTurf management, marketing, and technical activities in Dalton, Georgia, as AstroTurf Industries, Inc.

November 3, 1987: U.S. hearing, "NutraSweet: Health and Safety Concerns," Committee on Labor and Human Resources, Senator Howard Metzenbaum, chairman.

1988: A federal jury finds Monsanto Co.'s subsidiary, G.D. Searle & Co., negligent in testing and marketing of its Copper 7 intrauterine birth control device (IUD). The verdict followed the unsealing of internal documents regarding safety concerns about the IUD, which was used by nearly 10 million women between 1974 and 1986.

1990: EPA chemists allege fraud in Monsanto's 1979 dioxin study, which found exposure to the chemical doesn't increase cancer risks.

1990: Monsanto spends more than $405,000 to defeat California's pesticide regulation Proposition 128, known as the "Big Green" initiative. The initiative is aimed at phasing out the use of pesticides, including Monsanto's product alachlor, linked to cancer and global warming.

1990: With the help of Roundup, the agriculture division of Monsanto was significantly outperforming Monsanto's chemicals division in terms of operating income, and the gap was increasing. But as Glover notes, while "such a blockbuster product uncorks a fountain of revenue", it "also creates an uncomfortable dependency on the commercial fortunes of a single brand. Monsanto's management knew that the last of the patents protecting Roundup in the United States, its biggest market, would expire in the year 2000, opening the field to potential competitors. The company urgently needed a strategy to negotiate this hurdle and prolong the useful life of its 'cash cow'."

1991: Monsanto is fined $1.2 million for trying to conceal discharge of contaminated waste water into the Mystic River in Connecticut.

1993: By April, the Department of Veterans Affairs had only compensated 486 victims, although it had received disability **CLAIMS** from 39,419 veteran soldiers who had been exposed to monsanto's Agent Orange while serving in Vietnam. No compensation has been paid to Vietnamese civilians and though some compensation was paid to U.S. veterans, according to William Sanjour, who led the Toxic Waste Division of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), "thousands of veterans were disallowed benefits" because "Monsanto studies showed that dioxin [as found in Agent Orange] was not a human carcinogen." An EPA colleague discovered that Monsanto had apparently falsified the data in their studies. Sanjour says, "If [the studies] were done correctly, they would have reached just the opposite result."

1994: the first of Monsanto's biotech products to make it to market was not a GMO crop but Monsanto's controversial GMO cattle drug, bovine growth hormone — called rBGH or rBST, Monsanto granted regulatory approval for its first biotech product, a dairy cow hormone. Monsanto developed a recombinant version of BST, brand-named Posilac bovine somatropin (rBST/rBGH), which is produced through a genetically engineered GMO E. coli bacteria. Synthetic Bovine Growth Hormone (rBGH), approved by the FDA for commercial sale in 1994, despite strong concerns about its safety. Since then, Monsanto has sued small dairy companies that advertised their products as free of the artificial hormone, including Ben & Jerry's ice cream and most recently bringing a lawsuit against Oakhurst Dairy in Maine.

1995: Genetically engineered canola (rapeseed) which is tolerant to Monsanto's Roundup herbicide was first introduced to Canada. Today 80% of the acres sown are genetically modified canola.

1995: Monsanto is sued after allegedly supplying radioactive material for a controversial study which involved feeding radioactive iron to 829 pregnant women.

1995: Monsanto ranked 5th among U.S. corporations in EPA's Toxic Release Inventory, having discharged 37 million pounds of toxic chemicals into the air, land, water and underground. Monsanto was ordered to pay $41.1 million to a waste management company in Texas due to concerns over hazardous waste dumping.

1995: The Safe Shoppers Bible says that Monsanto's Ortho Weed-B-Gon Lawn Weed Killer contains a known carcinogen, 2,4 D. Monsanto officials argue that 'numerous studies have found no link to cancer'.

1996: Monsanto introduces its first biotech crop, Roundup Ready soybeans, which tolerate spraying of Roundup herbicide, and biotech BT cotton engineered to resist insect damage.

As Monsanto had moved into biotechnology, its executives had the opportunity to create a new narrative for Monsanto. They begun to portray genetic engineering as a ground-breaking technology that could contribute to feeding a hungry world. Monsanto executive Robb Fraley, who was head of the plant molecular biology research team, is also said to have hyped the potential of GMO crops within the company, as a once-in-a-generation opportunity for Monsanto to dominate a whole new industry, invoking the monopoly success of Microsoft as a powerful analogy. But, according to Glover, the more down-to-earth pitch to fellow executives was that "genetic engineering offered the best prospect of preserving the commercial life of Monsanto's most important product, Roundup in the face of the challenges Monsanto would face once the patent expired."

Monsanto eventually achieved this by introducing into crop plants genes that give resistance to glyphosate (the active ingredient in Roundup). This meant farmers could spray Roundup onto their fields as a weedkiller even during the growing season without harming the crop. This allowed Monsanto to "significantly expand the market for Roundup and, more importantly, help Monsanto to negotiate the expiry of its glyphosate patents, on which such a large slice of Monsanto's income depended." With glyphosate-tolerant GMO crops, Monsanto was able to preserve its dominant share of the glyphosate market through a marketing strategy that would couple proprietary "Roundup Ready" seeds with continued sales of Roundup.

1996-1999: Monsanto sold off its plastics business to Bayer in 1996, and its phenylalanine facilities to Great Lakes Chemical Corporation (GLC) in 1999. Much of the rest of its chemicals division was spun off in late 1997 as Solutia. This helped Monsanto distance itself to some extent not only from direct financial liability for the historical core of its business but also from its controversial production and contamination legacy.

1997: Monsanto introduces new GMO canola (rapeseed), GMO cotton and GMO corn (maize), and buys foundation seed companies.

1997: Monsanto spins off its industrial chemical and fibers business into Solutia Inc. amid complaints and legal claims about pollution from its plants. Solutia was spun off from Monsanto as a way for Monsanto to divest itself of billions of dollars in environmental cleanup costs and other liabilities for its past actions — liabilities that eventually forced Solutia to seek Chapter 11 bankruptcy. According to a spokesman for Solutia, "(Monsanto) sort of cherry-picked what they wanted and threw in all kinds of cats and dogs as part of a going-away present," including $1 billion in debt and environmental and litigation costs. Some pre-bankruptcy Solutia equity holders allege Solutia was set up fraudulently as it was always doomed to fail under the financial weight of Monsanto's liabilities.

1997: The New York State Attorney General took Monsanto to court and Monsanto was subsequently forced to stop claiming that Roundup is "biodegradable" and "environmentally friendly".

1997: The Seattle Times reports that Monsanto sold 6,000 tons of contaminated waste to Idaho fertilizer companies, which contained the carcinogenic heavy metal cadmium, believed to cause cancer, kidney disease, neurological dysfunction and birth defects.

1997: Through a process of mergers and spin-offs between 1997 and 2002, Monsanto made a transition from chemical giant to biotech giant. Monsanto's corporate strategy led them for the first time to acquire seed companies. During the 1990s Monsanto spent $10 billion globally buying up seed companies — a push that continues to this day. It has purchased, for example, Holden's Foundations Seeds, Seminis — the largest seed company not producing corn or soybeans in the world, the Dutch seed company De Ruiter Seeds, and the big cotton seed firm Delta & Pine. As a result, Monsanto is now the world's largest seed company, accounting for almost a quarter of the global proprietary seed market.

1998: Monsanto introduces Roundup Ready corn (maize).

1998: In the UK, Monsanto purchased the seed company Plant Breeding International (PBI) Cambridge, a major UK based cereals and potato breeder, which Monsanto then merged with its existing UK agri-chemicals and GMO research businesses to form Monsanto UK Ltd. Monsanto UK has carried out field trials of glyphosate-tolerant sugar / fodder beet, glyphosate-tolerant oilseed rape, and glyphosate-tolerant and male sterility / fertility restorer oilseed rape.